December 13, 2019

Tumor Microenvironment: How brain tumors grow and elude treatment

Brain tumors cannot sustain themselves on their own. They need blood supply, nutrients, and waste removal, just like any other tissue in a body. So around of a brain tumor, or any other malignant tumor, there is a border zone that oncologists call the tumor microenvironment where the tumor grows and interacts with the body. Scientists study the tumor microenvironment to learn how brain tumors seize resources from healthy bodies to fuel their growth, elude the immune system, and regrow after surgeries or treatments.

Tumors typically induce the body to create more blood vessels as they grow. This process is called angiogenesis, which comes from Greek words for container, angos, and for origin, genesis. Because tumors grow unchecked, they consume a lot of oxygen and nutrition. On their own they will outgrow their pre-existing blood supply. So they release chemicals that tell the body to create new blood vessels, and in this way tumors begin to make a microenvironment that is more suitable to tumor growth at the expense of the rest of the body.

A promising area of research in cancer treatment is targeting treatments at angiogenesis rather than directly at tumors themselves. This strategy aims to starve tumors of the nutrients they need to grow. One benefit of this approach is that tumors tend to mutate quickly and develop drug resistance over the course of treatment, whereas the cells that make up tumor blood vessels behave more predictably in response to drugs.

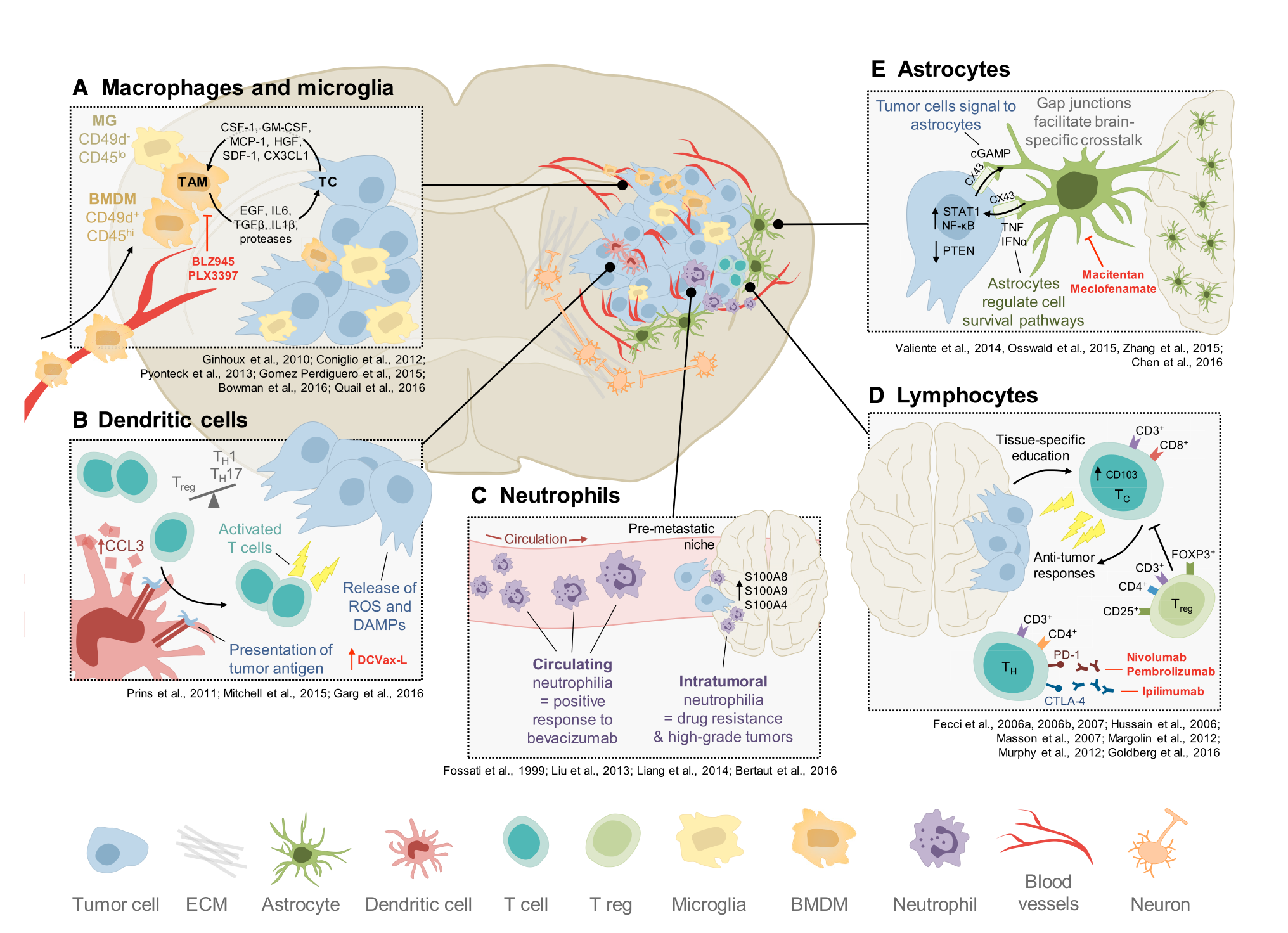

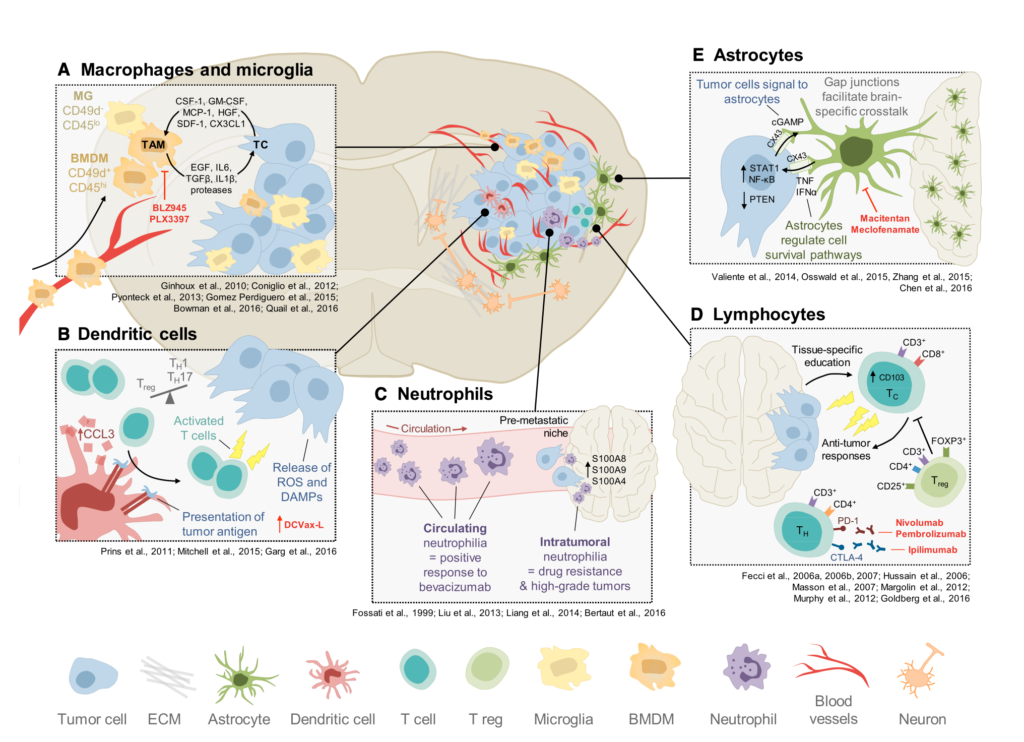

A second trait of of the tumor microenvironment is a group of cells called tumor-associated macrophages(TAMs) that hijack healthy body functions. These cells are originally a part of the immune system but they seem to get co-opted by tumors for more dubious purposes. They are present in large numbers in the tumor microenvironment and rather than helping fight tumor growth, instead seem to contribute to it. They send out signals to promote angiogenesis and block anti-tumor activity by the immune system. Some treatments seek to reprogram TAMs so they take on a cancer-fighting aspect.

A third defining feature of the tumor microenvironment is oxygen-deprivation, also known as hypoxia, and tissues that prefer oxygen-poor environments (unlike most healthy tissue). Brain tumors contain a number of proteins that thrive without oxygen, and the inner cores of brain tumors exhibit a greater degree of hypoxia than their outer regions. However, a researcher team at the National University of Taiwan found that aggressive brain tumors show more signs of hypoxia at the edge than other cancers do. In any case, these oxygen-deprived regions are harder to deliver effective doses of chemo therapy and radiation, and because of this, treatment strategies may need to take this into account in order to prevent recurrences.